A Strategic Guide to MVP Feature Prioritization with MVP Examples

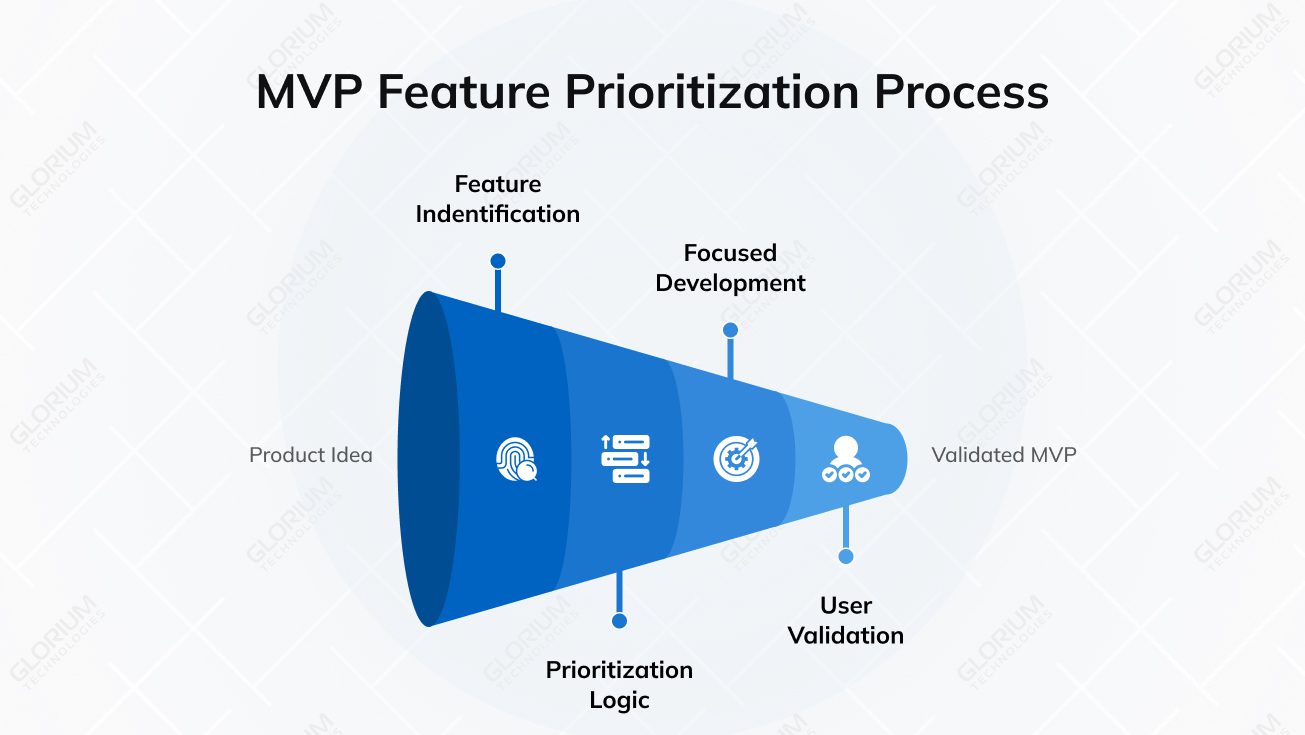

Turning a product idea into a first version is rarely as simple as it looks. Once planning starts, more and more features begin to feel ‘necessary,’ and the minimum viable product (MVP) quickly grows beyond its original purpose.

This is why MVP feature prioritization matters so much at an early stage. The main goal of an MVP is to answer questions, not showcase everything a product could become. Choosing features without a clear logic can lead to numerous challenges. As a result, teams spend more time and money than needed and still learn too little from real users.

A practical feature prioritization framework brings focus back to what matters most. Simply put, it helps teams decide which features support learning and how to move faster without overbuilding. Let’s break down how to prioritize MVP features with clarity, keep development focused, and, finally, validate ideas faster.

Content

First, let’s get to the basics. Feature prioritization appears quite different when working on an MVP. At this stage, it is not about ordering dozens of ideas or planning for the future. It is about making a few deliberate choices to prioritize features that help test whether the product should exist at all. Around 9% of startups fail only because they’ve created products that are not user-friendly.

Here is one of the good MVP examples: if you are building a travel app, the MVP should focus only on destination search and booking a stay. It is not the time to add more information about loyalty programs or personalized recommendations.

When providing the minimum viable product definition, one can say that it is the minimal version of a product that delivers value and allows you to learn from real users. The MVP concept is often mistaken for a rough or half-finished release. In reality, there is a valuable reason why this or that feature is included.

Problems typically arise when teams treat an MVP as if it were an actual product. An MVP is built to answer questions. An actual product is built to support growth and scale. Between those two lies the minimum marketable product, which adds stability and polish, allowing the solution to be offered to a wider audience. In such a scenario, things like customer support tools or payment optimizations are better left for the minimum marketable product (not MVP).

One in five startups fail in their first year, and one reason is that they do not address real customer needs early enough. This is the risk that MVP testing and feature prioritization are meant to reduce.

An MVP should focus on core functionality, rather than advanced features or future ideas. This is a pattern seen across many MVP examples: when the scope stays small, teams can see how users behave, collect useful feedback, and learn what actually works.

MVP vs actual product vs minimum marketable product

| Stage | Purpose | Feature Scope | Target Users | Outcome |

| MVP | Test the core idea | Core functionality only | Early users and early adopters | Clear insights and learning |

| Actual product | Support growth at scale | Broad and evolving features | Defined target market | Sustainable usage and growth |

| Minimum marketable product | Enable wider release | Stable, market-ready features | Paying customers | Early revenue and retention signals |

When these stages are clearly separated, feature prioritization becomes easier. The focus shifts from building more features to learning the right things at the right time.

At the MVP stage, budgets and timelines are shaped by the choices made early on. The main goal of feature prioritization is to help teams stay concentrated and avoid work that does not move the product forward.

One of the most common reasons startups fail is building products that do not meet real market needs. This is exactly the risk MVP feature prioritization helps reduce. Let’s go over some practical ways MVP feature prioritization helps drive cost savings and speed up a lot:

“Our first MVP took one year to build. Our second MVP took two months. We learned that more features did not equal a better product.”

Natalie Barbu, How We Built Our App in 2 Months: Lessons from Launching a Startup

All in all, when feature prioritization is done right, teams spend less time reacting and more time learning.

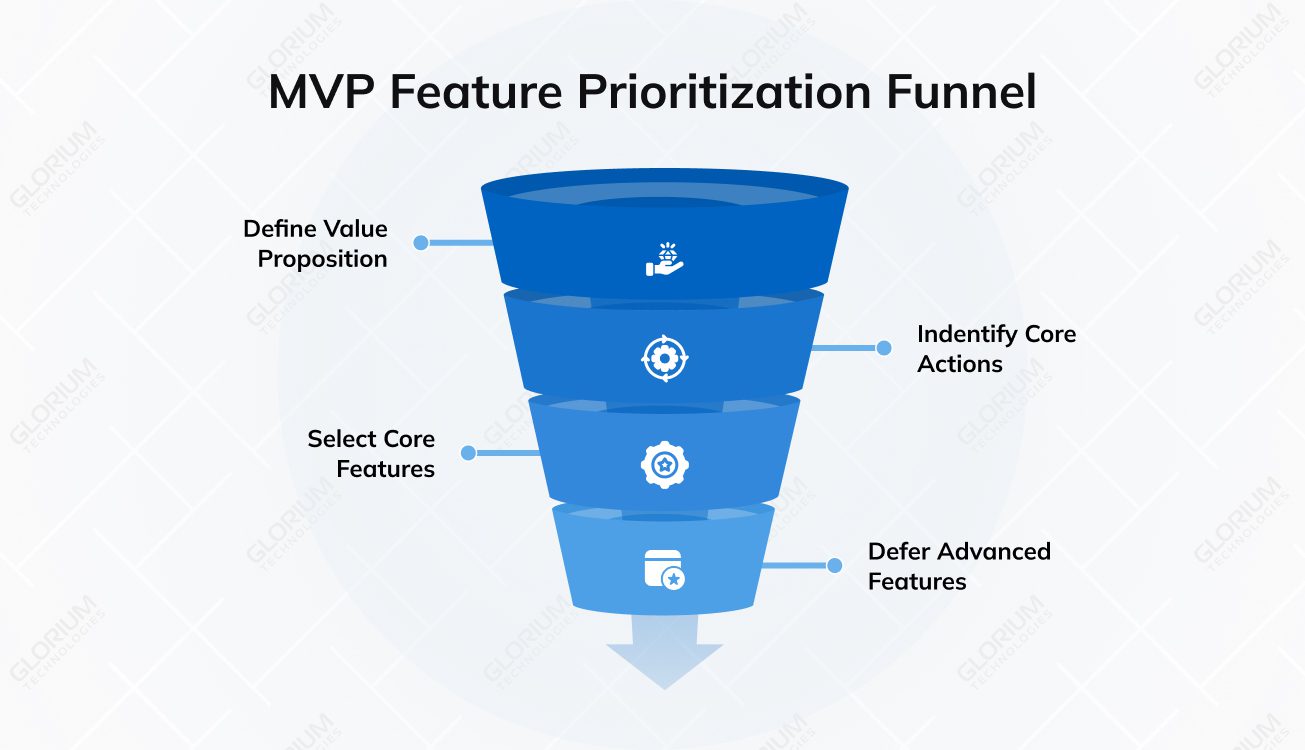

You do not need a complicated system to prioritize MVP features. What you need is a clear way to decide what belongs in the first release and what can wait. Here’s a simple rule that can save you time: if a feature does not allow you to test the idea, it is not part of the MVP. Below, you’ll see the detailed framework that paved the way for success for many MVPs.

You first need to understand the actual problems your target users are facing. What are the biggest customer pain points you are trying to solve? This is where you need to be specific. For example, “Planning trips is hard” is vague, but “People struggle to compare options quickly” is a more precise pain point you can build around. Once the pain points are clear, it is time to define your value proposition in a single sentence. What is the central promise you are making to the user? This keeps the team aligned as feature ideas pile up.

Next, list the few actions that must work for the product to deliver value. That is your product’s core functionality. For a travel app, for example, users may need to search, compare, and book. Once these actions are defined, they become the baseline for the MVP. If users cannot complete these core actions, the product cannot deliver value at this stage, regardless of any additional functionality.

Only after you define the problem, value proposition, and core user actions should you identify the core features of the MVP. Each feature should directly support a specific action and be relevant to the needs and expectations of your target audience.

In doing so, feature decisions become much easier. Remember that you are not debating opinions; you are matching features to a real user problem and a clear promise.

One of the most challenging aspects of MVP development is saying no. The thing is that teams rarely run out of ideas; they run out of focus. When that happens, everything can start to feel equally important, which makes it harder to distinguish what is essential from what is optional.

This is why it is critical to draw a clear line between basic features and advanced features. Basic features help users complete the primary task the product is designed to perform. Advanced features can make the experience nicer, but they are not required to test whether the idea works. If a feature does not help answer an important question, it can wait. If you look at real-world minimum viable product examples, you’ll see that early feature sets are often adjusted after launch. Teams learn which features actually matter and which ones can be removed.

Let’s say a real estate company is developing an MVP—a basic website for browsing listings. The first release could focus on browsing and requesting a viewing, without dashboards, automation, or deep analytics. The advanced features that sound so inviting and exciting could be added once the launch provides enough proof that they’re needed.

Another way to stay lean is to rely on existing tools rather than build everything from scratch. For instance, a travel MVP can use a standard payment provider. A real estate product can depend on a map service and listing APIs. It is not glamorous, but it is a chance to get feedback faster.

“You want people using your product. You want people telling you why it’s cr*p. You want people giving you as much feedback as possible.”

Mike (Starter Story interview), I Built 3 SaaS Apps to $200K MRR: Here’s My Exact Playbook

The same applies to building your own technology. Custom systems make sense when they create a real advantage or are central to the product’s core value. If they are not, push them to a later time. Good MVPs must always be focused; of course, they do a few things well, test the right assumptions, but leave the rest for future iterations.

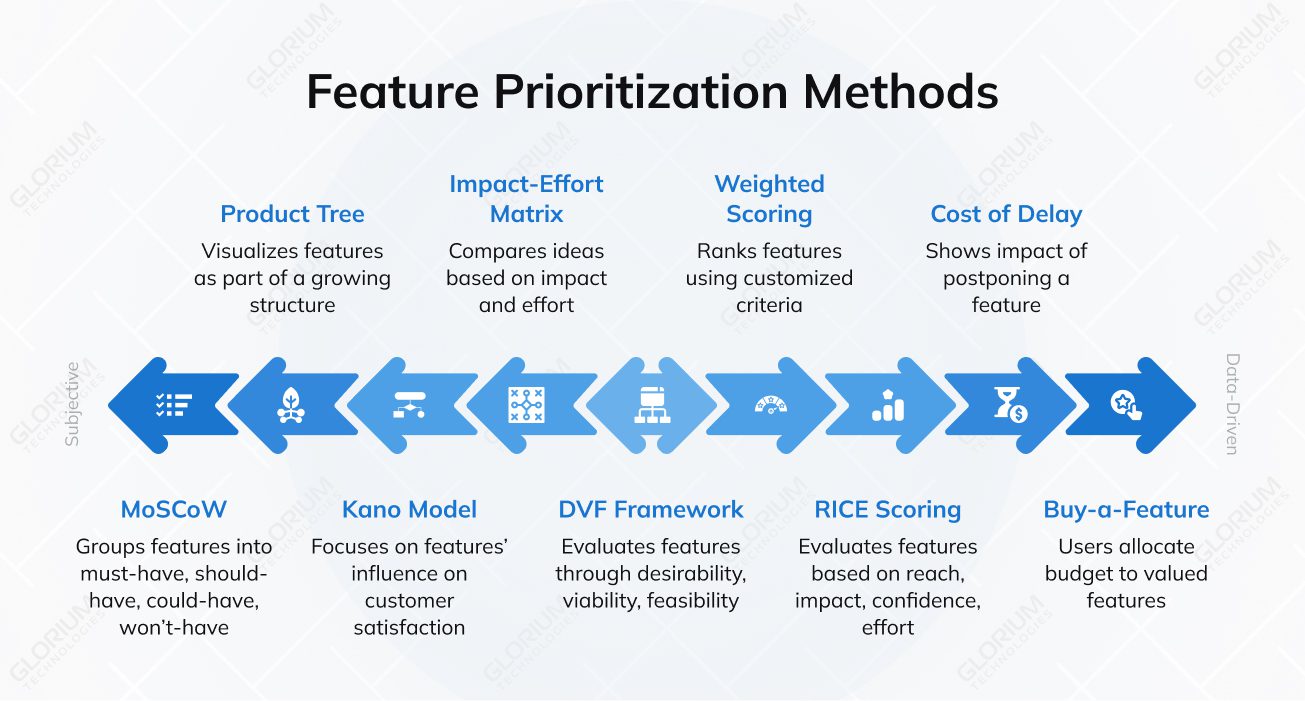

When teams work on a minimum viable product, feature decisions need structure. Prioritization methods help compare ideas and focus on what supports validation, rather than feature volume. These frameworks are often used to guide discussions and reduce subjective decision-making.

This method groups ideas into clear feature buckets: must-have, should-have, could-have, and won’t-have (at least for now). This approach helps protect essential features and keeps teams focused on basic functionality that supports validation. It works especially well when defining features for your MVP actually matter.

RICE scoring evaluates potential features based on reach, impact, confidence, and effort. This framework helps teams estimate how many users a feature can affect and whether it delivers the most value relative to the effort required. It is advantageous when early market research or usage data is available.

The primary objective of this method is to compare ideas based on their expected impact and implementation effort. For MVP planning, it helps teams identify quick wins and avoid committing to high-effort features too early. On top of that, this method supports faster learning and keeps scope under control.

The Kano model focuses on how features influence customer satisfaction. It distinguishes between essential features, performance features, and delighters. In an MVP context, this framework helps teams cover the basics first. After that, it becomes easier to decide which experience improvements can wait until later.

This framework evaluates features through three lenses: whether users want them, whether they support business goals, and whether they can realistically be built. This approach facilitates alignment between product ideas and technical constraints, as well as long-term business objectives. Simply put, it helps teams avoid building features that sound good on paper but do not make sense for the current stage of development.

It ranks features using customized criteria, such as user value, risk reduction, or strategic fit. The model enables teams to compare ideas objectively while still prioritizing what matters most to the business at the MVP stage.

This formula helps teams see what happens when a feature is postponed and gain a better understanding of how timing affects value. Some features lose value quickly if released too late; others can wait without a significant impact. For MVP planning, this method is useful when timing matters, such as testing demand, entering a new market, or learning from users before conditions change.

The product tree approach visualizes features as part of a growing structure, starting with the trunk and expanding outward. This helps teams stay focused on basic functionality and the core user journey, while clearly separating MVP scope from future ideas.

The Buy-a-Feature method asks users to allocate a limited budget to the features they value most. This approach helps teams gather user feedback early and understand which features resonate before development begins.

Each of these methods supports a different angle of decision-making, but the purpose is the same. They help teams decide what belongs in the MVP now and what should wait until there is clearer evidence. When looking at real MVP examples, successful teams rely on simple frameworks like these to stay focused and avoid overbuilding the initial version of the product.

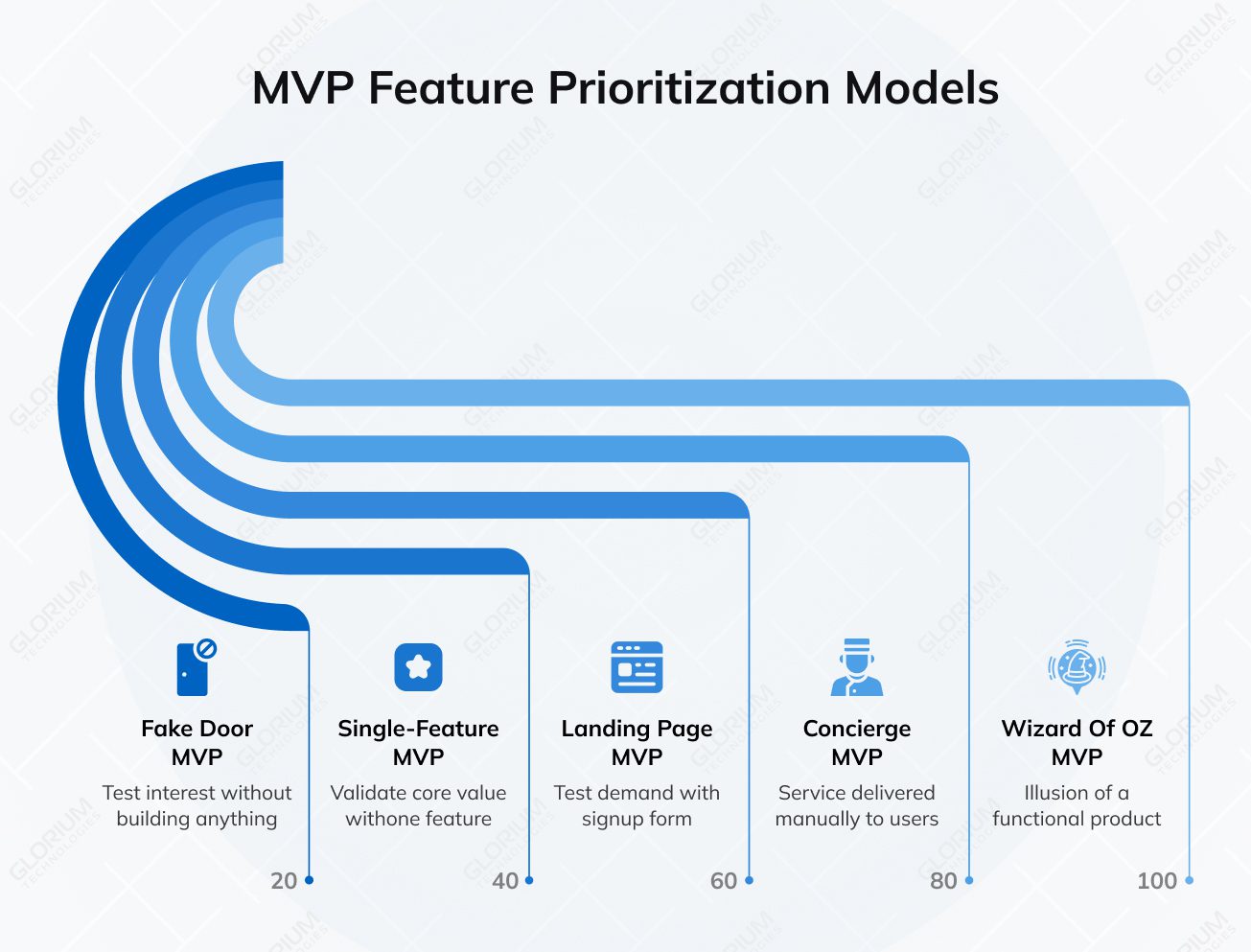

Each model is designed to answer a specific question, which naturally limits what needs to be built. Instead of guessing which features matter, teams can use these approaches to focus on real customer pains.

A Wizard of Oz MVP looks like a working product from the outside, but most of the logic is handled manually behind the scenes. Its main goal is learning. Simply put, this type creates an illusion of a functional product, but it greatly depends on manpower.

A well-known example often cited is Joe Gebbia’s early Airbnb work, in which listings and bookings were managed manually to test demand. In practice, a Wizard of Oz MVP creates space to observe how users behave, what confuses them, and which parts of the experience actually matter. Features that users ignore quickly fall off the priority list.

A Concierge MVP takes an even more hands-on approach. Instead of automating the process, the team delivers the service manually to a small group of real users. This works especially well when customer problems are complex or poorly understood.

In this case, early users interact directly with the team, so feedback is always more detailed. As a result, teams see which features are essential and which are just assumptions. But what is the difference between the Wizard of OZ and the Concierge MVP? It is all about transparency. With a Concierge MVP, users understand that a person is handling the service behind the scenes. In contrast, a Wizard of Oz MVP hides that manual work. It makes the product appear automated even though it is not.

A landing page MVP is probably the simplest way to test demand. Instead of building a product, teams present the idea clearly and see whether users respond. This can include a basic landing page, a short signup form, or even an explainer video, MVP, or demo video.

This model focuses on delivering one action that represents the product’s core value. It is a version of the product that was launched with only one (the most important) feature. Everything else is stripped away. This approach works well when the product idea can be reduced to one clear benefit. If users consistently engage with this model, it becomes easier to justify expanding the feature set. If not, the team can pivot without having invested heavily in secondary features.

Low-fidelity MVPs help test ideas ASAP and without incurring significant expenses. These can include wireframes, sketches, mockups, or simple workflows that show how the product should work. A simple MVP like this is often enough to uncover usability issues and misunderstandings.

However, a high-fidelity MVP looks and feels closer to a finished product. It can offer richer feedback, but it also takes more time and effort to build. A good MVP is not defined by polish, but by how effectively it answers the right questions.

A fake door MVP lets teams test interest without building anything first. Users see a feature option, and the team simply tracks how many people try to use it. That reaction alone can say a lot about demand.

A crowdfunding MVP takes this idea further by asking users to invest their money in their interest. Instead of measuring clicks, it shows whether people are actually willing to pay. Together, these approaches give clear signals about which features deserve attention and which ones can wait.

MVP models overview

| Mvp Model | What It Validates | Typical Features | Best Use Case |

| Wizard of Oz MVP | User behavior and demand | Manual workflows behind a polished interface | Early validation without full automation |

| Concierge MVP | Customer needs and workflows | Human-delivered service | Complex or trust-based products |

| Landing page MVP | Market interest | Signup forms, explainer or demo videos | Testing demand and messaging |

| Single feature MVP | Core value | One essential function | Clear, focused product ideas |

| Low-fidelity MVP | Usability and understanding | Wireframes, mockups | Early-stage concept testing |

| High-fidelity MVP | Experience and engagement | Near-real product flows | Later-stage validation |

| Fake door MVP | Feature demand | Clickable but unavailable options | Testing interest before building |

| Crowdfunding MVP | Willingness to pay | Campaign pages, early offers | Revenue validation |

How to Adjust MVP Feature Priorities Using Honest User Feedback

The global MVP development market is growing, and forecasts are showing an increase from about $288 million in 2024 to over $540 million by the early 2030s. This reflects how widely MVPs are used to reduce risk and speed up market entry. But launching an MVP is only the beginning. Even when an MVP is live, feature prioritization does not stop. The difference is in how decisions are made. Early assumptions give way to real usage, and that is when priorities start to shift.

The first step is to gather feedback with a purpose. Rather than asking users what features they want, pay attention to how they actually use the product. Where do they slow down? What do they skip? Which actions do they repeat without prompting? This kind of real user feedback is far more reliable than opinions.

However, you should keep in mind that not all input deserves the same weight. Customer feedback often includes suggestions, but suggestions on their own should not drive decisions. Patterns matter more when multiple users struggle with the same step or depend on the same feature, which is undoubtedly worth attention.

So, when the feedback is collected, it is high time to analyze the feature list and define priorities:

The good news is that there’s no need to react to every comment. You can often learn a lot from a simple WordPress website just by watching how people use it over time. When teams collect user feedback this way, the MVP can improve without drifting off track.

The next steps are often the most challenging. The first version has already served its purpose, but the next iteration requires more careful choices, not more features.

The shift from an MVP version to a more complete product should start with a clear review of what the MVP validated. Some features proved their value. Others were useful only for testing assumptions. For example, a travel MVP may confirm that users frequently search and book trips, while rarely using saved itineraries. In that case, booking-related improvements deserve attention, and secondary features can wait.

In MVP development, progress should be guided by evidence. Features that users return to are strong candidates for the next release. However, advanced functionality with low engagement should be postponed. As MVP product development continues, scope creep becomes harder to control because new ideas are coming from many directions at once.

A consistent MVP approach helps teams evaluate each feature against what already works and where the product is heading. This is also where working with an experienced development team, like Glorium Technologies, adds value. Our engineering expertise helps teams implement a clear MVP strategy, validate features, and avoid unnecessary complexity.

Your startup idea might be out-of-this-world and turn into exactly what people need. But if you need to communicate a value proposition, you can do without a demo video MVP first. The latter must demonstrate your product’s future portrait and the features it must possess. Here, every choice you make will shape the product’s direction, its budget, and long-term development path. That’s why teaming up with Glorium Technologies for top-notch MVP development services can be the smartest move to take. We combine strategic thinking, user validation, and technical execution along with our end-to-end support to help founders make informed feature choices from the very start.

With over 15+ years of product and engineering work, Glorium Technologies helps teams shape a clear MVP scope, turn assumptions into testable hypotheses, and align early features with real user behavior. We don’t build an initial version based on assumptions; our approach guarantees that each core feature contributes to validated learning and meaningful outcomes.

We have a few successful examples. Let’s briefly review them:

Validating a niche proptech solution: from MVP to market

In this project, our team focused the MVP on a single real estate workflow: browsing listings and managing renovation projects. This allowed demand to be tested early and feedback to come from real users instead of assumptions. By deliberately excluding secondary features that didn’t support this flow, the concept was validated more quickly, providing the product with a clearer path to market.

Clinically-validated fertility platform: MVP to full-scale

For the fertility tracker, our team built the MVP around clinical validation and patient trust. This focus helped shape a reliable core experience from the start and made it easier to scale later without losing sight of safety, regulatory needs, or usability.

For early-stage teams, this kind of partnership helps set priorities faster and avoid costly detours. For late-stage teams, it supports more disciplined decision-making as products evolve and scale.

Are you unsure which features truly belong in your MVP? Our team can help you sort through ideas, priorities, and constraints to define a focused MVP that makes sense. Reach out to us to get expert support and start moving forward with a clear plan from the very first step.

The most reliable way is to limit the MVP to just the core components needed to test the idea. Every feature should answer a specific question about user behavior. When teams lose that focus and add new features, the MVP stops being a learning tool and starts drifting toward a full product.

An MVP should be built for a defined target audience, usually early adopters. These users are more willing to share feedback. When you try to appeal to a broad group too early, it often leads to vague priorities and weak signals from potential users.

A spike is an internal experiment, which pursues one goal: to explore technical uncertainty. It is not meant for users. An MVP feature is part of a minimum viable product and exists to validate demand, usability, or value in real conditions. Spikes answer engineering questions, and the main goal of MVP features is to answer product questions.

Feedback should be evaluated through patterns. When the same behavior shows up across users, it signals where priorities should change. This is how teams move closer to a successful minimum viable product: they use evidence, not assumptions, to guide decisions.

It’s simple – technical work should support learning. Even on a simple website, if infrastructure improvements help users complete core tasks more effectively, they belong in the MVP. If they do not affect user experience, this means they can wait until after the MVP stage.

Good prioritization shows in how people actually use the product, especially when they choose it over existing services. When users complete key tasks and keep coming back, that matters far more than how many features exist. These signals often explain why some startups fail, but others learn fast and adjust early.

Professionals in this area help teams make early trade-offs with more confidence. That often means cutting scope, questioning assumptions, and learning from successful MVP examples (from different industries). An outside perspective makes it easier to spot common mistakes and stay focused on what actually needs to be built first.